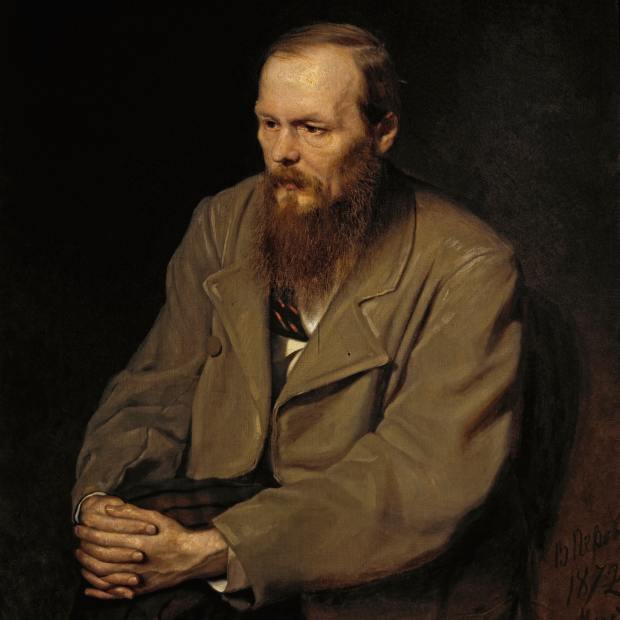

Every year, about the time when fall starts getting very chilly and threatens to turn into winter, I get the urge to tackle a big classic novel. I don’t always give into it. Often when I do it’s a Dickens novel. Last year it was Moby Dick. This year the urge hit, and to my surprise the book I suddenly wanted to read was The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky. It wasn’t on my list of classics to read soon, and I didn’t even own a copy of the book.

I wish I could remember exactly what prompted me to decide I needed to read this book urgently, but I can’t. I think it was a lot of little mentions of Dostoevsky here and there, and of Russian literature in general.

I do remember one specific mention of it this year, while I was re-reading Slaughterhouse Five in April:

“Rosewater said an interesting thing to Billy one time about a book that wasn’t science fiction. He said that everything there was to know about life was in The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky.”

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

Anyway, one way or another, I decided to read it for myself, and see if everything there was to know about life really could be found in its pages.

I chose to tackle The Brothers Karamazov the way I read Moby Dick, and The Lord of the Rings trilogy: by getting the audiobook and “reading along” with it. It’s a lovely way to read classic tomes that are a bit daunting. You pick out a good narrator, make sure your translation matches it, and sit back and read along as they read it to you. I find I stay more focused and don’t get lost if I’m following along with a print copy, instead of just trying to listen. I ended up reading along with about half the book, and reading on my own for the other half – mixing it up chapter by chapter depending on what I felt like that day. I chose the Constantine Gregory narration – he is a wonderful narrator. It uses the Constance Garnett translation, which was harder to find that I expected. (I ended up with the Barnes and Noble Classics edition.)

There is so much humanity in this novel. The Vonnegut quote really stuck with me while I was reading, and it’s absolutely true – there are huge themes of religion and god and good vs. evil and conscience and family and love. But there are also so many other things packed into the story of three brothers and the murder of their father. It seemed as if every page had an insight into human character and temperament that was instantly recognizable as truth despite the 134 years that have passed since it was published. It’s one of the most impressive novels I’ve ever read, and I was surprised how much I enjoyed reading it.

The only thing I didn’t enjoy about the novel is the lack of good female characters. The male characters are so varied, and most are multi-dimensional and developed well throughout the novel. Katya is the best we get, but she’s still a bit insufferable. Grushenka is the pits. There aren’t really that many other females, but all of them seem to be parodies of ridiculous females driven to jealousy, weakness of mind, and/or hysterics. I’m actually most fond of Lizaveta, she at least seems to be an independent spirit, in the brief glimpse we get into her short tragic life.

Besides my affection for the short stories of Chekhov, this was my first novel from the Major Russians. I admit that I feel a little relieved not to have this glaring hole in my classics education any longer, but there’s a lot more time to spend with them as well. I think Anna Karenina or War and Peace will be next, whenever the giant classic inspiration strikes again. Or perhaps I’ll surprised myself and choose Gogol.

As usual, I’ll leave you with some of my favorite lines and passages. (The page numbers reference the Barnes and Noble Classics edition.)

“As a general rule, people, even the wicked, are much more naive and simple-hearted than we suppose. And we ourselves are, too.” – page 17

“I think if the devil doesn’t exist, but man has created him, he has created him in his own image and likeness.” – page 221

“In truth we are each responsible to all for all.” – page 274

“At some thoughts one stands perplexed, especially at the sight of men’s sin, and wonders whether one should use force or humble love. Always decide to use humble love. If you resolve on that once and for all, you may subdue the whole world. Loving humility is marvelously strong, the strongest of all things and there is nothing else like it.” – page 294

“I’ve been asleep and dreamt I was driving over the snow with bells, and I dozed. I was with some one I loved, with you. And far, far away. I was holding you and kissing you, nestling close to you. I was cold, and the snow glistened … you know how the snow glistens at night when the moon shines. It was as though I was not on earth. I woke up, and my dear one is close to me. How sweet that is…” – page 404

“It seemed that all that was wrong with him was that he had a better opinion of himself than his ability warranted.” – page 415

“You must know that there is nothing higher and stronger and more wholesome and good for life in the future than some good memory, especially a memory of childhood, of home. People talk to you a great deal about your education, but some good, sacred memory, preserved from childhood, is perhaps the best education. If a man carries many such memories with him into life, he is safe to the end of his days, and if one has only one good memory left in one’s heart, even that may sometime be the means of saving us.” -page 700